In this surreal and unpredictable time in our society “lying” somehow became an accepted norm that we need to be mindful of as we navigate and communicate in our social and political circles. On any given day, up is down and down is up or rather up is left and down is right and everything said or written is either: 1) taken out of context or 2) unequivocally denied. But—What does it mean to lie?

“To lie is not only to say what isn’t true. It is also and above all to say more than is true, and as far as the human heart is concerned, to express more than one feels. This is what we all do, every day, to simplify life.”*

Is Camus on point? Do we tend to express more than we feel and more than what is necessary?—Absolutely. Socially speaking, it will never cease to amaze me how much information—personal intimate information—individuals are willing to divulge to complete strangers. And yet, are shocked when negative reactions may happen as a result.

And, there does seem to be a need to say more than what is true. For some reason, personal experiences, family dramas, professional or academic successes even failures are often works of historical fiction rather than a retelling of actual events. Is it better even acceptable to add a little color and pizzazz to an otherwise ordinary experience? Making ourselves a bit more interesting even though it isn’t true? Do we accept these tall tales as part of some undefined social contract? Everyone tells little white lies, right? To spare people’s feelings from being hurt or to avoid conflict; it does make life easier. Is this what Camus meant by “what we all do every day to simplify life?”

I believe that, in general, we do tend to say more than we need to say. Conversely however, how “exact” or detailed do we need to be without “lying,” or being intentionally hurtful or deceptive? This is a question we must consider and answer. Opinions and feelings are one thing; facts are quite another.

In my novel, Someday, the main characters are flawed in many ways and yet are likable even lovable, but they are struggling with authenticity; lying not only to the ones in their intimate circle but more importantly to themselves. Despite their intimate failures, all are seeking the truth and defending themselves from “untruths.” We complicate our lives simply by saying more than what we need to say.

Fictional storytelling is one thing as is our non-fictional relationships with partners, family, and friends—what we choose to tell people about our pasts, our relationships, our careers, our financial well-being. But when the art of lying spreads like wildfire through our coveted democratic institutions and news media channels that threatens the heart and lifeblood of our democracy, we are treading in dangerous water if we don’t take individual and collective responsibility to call out fiction from fact.

What is it that we need to know? I will go out on a limb by asserting—all journalists know the essential core elements with respect to reporting events: Who, What, Where, When, How, and [sometimes] Why. I emphasized why because “Why” is tricky unless it is explained based on concrete evidence. Otherwise why is speculative, subjective and without “facts” highly opinionated and must be stressed upfront that it is one possible theory and not fact.

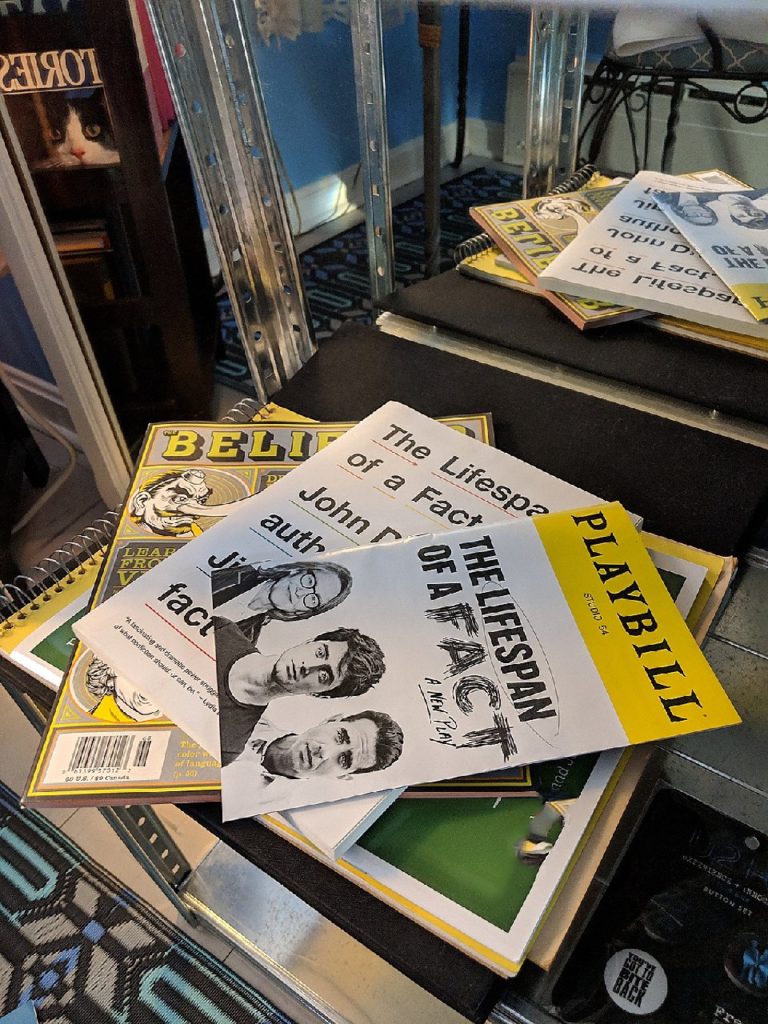

Last October I saw the play, The Lifespan of a Fact, based on the book of the same name that is based on an account of what took place between a seasoned essayist and his fact-checker, a Harvard graduate.

When I first read the book, I was amused at the hilariously ridiculous and yet at the same time concerning “fact” that the essayist showed little or no regard for the “facts” or the “truth.” When the fact-checker called him out on the numerous factual errors and passing off fabrications as facts, he scoffed, belittled and questioned his fact-checker’s experience and integrity. To me, changing facts or manufacturing them, to support a theory or paint a picture is morally bereft—no matter who it is.

Now more than ever, we all need to be brutally aware and accurately informed. We need to be astute observers, listeners and essentially our own fact-checkers. Because the very foundation that right now ensures our freedom and our liberty that we all enjoy may very well become an historical fact that no longer exists.

###

________________________________________________

*Camus, Albert. “Preface to The Stranger 1956.” Lyrical & Critical Essays. New York: Vintage Books, 1970, pp. 335-356.